The year was 1964. The place was New York City. After waking up, the first order of business for Beth Holcombe was to make sure her uniform was clean and pressed for her 6:00 p.m. flight to Paris. After a midday nap to prepare for the seven-hour trip overseas, she made her way to JFK airport for a briefing from the service manager and captain about the night’s flying conditions.

Being a TWA flight attendant or, at the time, a “hostess,” in the early 1960s was surely a glamorous job, and one that Holcombe and many others took great pride in. Even with the less-glamorous tasks like checking parsley amounts for in-flight meals—not to mention having to stay awake throughout the duration of an international flight—the hostesses lived up to their job titles and did it all with charm and hospitality.

They didn’t do it because it was easy—the hostesses typically made about $220 a month and were seriously sleep deprived—they did it because it was magical.

“It was truly a dream job,” Holcombe recalled, now president of Silver Wings International Inc., a group dedicated to celebrating retired TWA flight attendants. “Every flight was a different experience. It wasn’t like going to the same job every day and putting up with the same people. We got to see the world for nothing.”

Holcombe knew she wanted to be a TWA hostess since the early age of eight after a short flight from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh to visit her grandmother, during which she was enthralled by the genuine and gentle nature of the women.

“I liked how snappy they looked in their uniforms. I think about this often—the question of ‘why’ I wanted to work for them—they were just super nice people, and that has been my way of going about life: being nice to people,” she said.

Also romanticized by flight itself, Holcombe found peace up in the clouds, a mode of transport that moved both minds and bodies.

“There was something about it that appealed to me,” Holcombe said. “Flying over the earth and looking down that far, seeing what you could see and how you get to somewhere just like that. You’re somewhere, then you wait for a while, and then you’re off and you’re someplace else. It was just so exciting, and it still is today.”

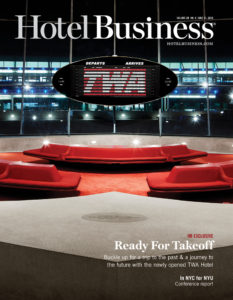

It really is just as exciting in 2019, and now, has an estimated $265-million project to prove it. After its close in 2001 and sitting dormant for almost 20 years, restoring Eero Saarinen’s iconic TWA terminal into a hotel wasn’t just about preserving a New York landmark, but preserving an era.

“We brought the building back to exactly as it was in 1962, down to the penny tile on the floor; we didn’t leave a stone unturned,” said Tyler Morse, CEO/managing partner, MCR/Morse Development. “It harkens back to an age when air travel was very special—not everyone was traveling on airplanes like they are now, and anything was possible in ’62.”

A lot was riding on the restoration: the memories of thousands of former TWA employees to start, as well as the expectations of aviation fanatics across the globe. Morse was set on doing it the right way, meaning no shortcuts and absolutely no faking it.

“I think people can spot authenticity, and I couldn’t outsource talking to these former TWA employees to a consulting firm or give it to a branding agency,” Morse told Hotel Business. “You need to do the work. I think a lot of people in today’s world don’t do the work; they try to outsource the work, and the consumer can see that. People can spot a fake a mile away.”

CLOCKWISE, FROM TOP LETF: A view of iconic Flight Tube No. 2

Eero Saarinen’s soaring terminal serves as the heart of the TWA Hotel.

Two brand new wings behind Eero Saarinen’s historic terminal house the TWA Hotel’s 512 guestrooms.

Morse spoke with approximately 1,000 former TWA employees with similar sentiments as Holcombe, visited the TWA Museum in Kansas City, read 12 books on Howard Hughes, and attended numerous TWA memorabilia auctions. Despite his preparedness, no amount of education could alleviate the fact that this was a sizable task, one that would take not only passion but the backing of an entire city.

“It really was not about getting people on board; the project was just so daunting and so complicated,” Morse explained.

It took 22 government agencies, a New York municipal process called ULURP (a public review process concerning land use and zoning laws), an FAA-required environmental assessment that took about a year, 14 preservationist groups and 18 workforce employment programs, plus the blessing of Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (now the owner and operator of the hotel).

“But I just love the building,” Morse said. “I said, ‘Damn the torpedoes’ and went for it anyway.”

That was just the start, however. Some $65 million was used to remove the asbestos, lead paint and change the HVAC and plumbing systems. But the development began even before getting the building up to code. It began at the very beginning—studying Eero Saarinen’s original drawings.

“Any project we do, we start with research,” said Richard W. Southwick, partner/director of historic preservation, Beyer Blinder Belle.

But this was different. This project had to be historically accurate, it had to honor Saarinen’s intentions, and it had to not just mirror, but transport guests to 1962. It began at Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University, where Southwick and his team used Saarinen’s original drawings to develop base plans and to see how details of the building were constructed—for example, the chili-pepper red Sunken Lounge.

“When that was reconstructed and rebuilt, the materials and layout for the original shop drawings were very helpful,” Southwick said. “We were very lucky to have found a lot of the original sample boards, and the red carpet was still red—it did not degrade over the years from UV,” Southwick said.

But there wasn’t much to sift through—only 60 drawings to be exact, hardly the amount needed for a fully developed project.

“It’s only 60 drawings, 60 pieces of paper for the entirety of the building,” Morse noted. “Today, you can’t build a doghouse with 60 architectural drawings.”

However, it surely seems, Saarinen was efficient enough for it to work.

“It’s pretty neat what they were able to build and do with very little paperwork,” Morse continued. “It was really more artists and craftsmen, and the building itself is more a piece of art than it is an airplane terminal. There are no right angles in the building. Right angles are very easy to draw, easy to build, easy to execute; curves are not. The level and amount of curves in the building makes it wonderful, but we never really thought about that as much until we had to go restore all of them.”

Historic photographs were also helpful in determining what should be restored and were in the period of significance (1962-1968—when the final part of Saarinen’s original design was executed). Photographs also helped with remediation details, showing workers doing repairs, especially in the concrete.

“We saw photographs from 1963, a year after the building was opened, when people were doing repairs of the skylight slits,” Southwick said. “The concrete had always leaked, and there’s a fundamental design or construction era of how those were put in, so we replaced those.”

A 25-year project for Southwick, his heart was invested in the terminal prior to any of these updates. After the building was landmarked in 2004, Southwick worked with Port Authority and New York’s State Historic Preservation Office to determine exactly which parts of the building should be restored versus which parts should be reinvented.

For example, the lower and upper parts of the hotel’s lobby, the TWA first class Ambassador Club lounge and ticket halls in the main entrance, were all full and authentic restorations, while other less-historically significant features like the shops or other areas with more changes over time were referred to as “rehabilitation zones.”

“The whole building was remapped, which guided the plans for the new buildings,” Southwick said. “It was referential but certainly contemporary. They needed to reflect the year those were built rather than replicate what Saarinen’s design might have been.”

The two new structures on either side of the restored terminal rise 14 stories and comprise the hotel’s 512 guestrooms. The buildings are also some of the greenest in the state, with a cogeneration plant taking the hotel off the JFK electrical grid. All the power is provided on top of the north hotel tower, earning the building LEED-Certified Gold credentials.

As for its design, Southwick describes the two new buildings as modest backdrops to Saarinen’s terminal, but also, extensions of its grandeur.

“They act almost as a back curtain on the stage if you think of the main actor being the terminal. These create a neutral background for the iconic building to really stand out. Once you get inside though, it really does continue the ethos of the 1962 flight center,” Southwick said.

Inside tells a story of its own; everything from the details of the design, to the amenities, to the unmissable 1958 Lockheed Constellation aircraft-turned-cocktail-lounge parked outside of the original terminal.

“There’s nothing else like this in the world,” said Mike Suomi, principal/VP of interior design, Stonehill Taylor, the NY-based design firm responsible for the interior design of the hotel’s guestrooms and public spaces. “As a hotel designer, it’s a unique experience to work on something that is so singular and iconic where our concept came entirely out of the history of the building.”

Sourcing inspiration from history is no easy feat, and while the history may have provided a starting point and reference throughout the development, ensuring historical accuracy was something all teams took seriously.

Some 600 rotary-dial phones, 50 old flight attendant uniforms, original David Klein TWA posters, Life and Time magazines, and old newspaper articles were just some of the vintage materials purchased online, many of which were purchased on eBay.

“We felt, and Tyler felt, very strongly about putting authentic Eero Saarinen pieces in each room, which was a very aggressive conceptual starting point,” Suomi said. “They’re not the typical thing that room purchasing agents or hotels can afford, but Tyler and the design team worked hard to achieve that, and we began designing around that, using it as a core.”

The design team sourced many of these furniture pieces from Knoll—which still produces and authorizes Saarinen’s products, like his famous Saarinen Womb Chair, Tulip Table and Executive Chair—and from other U.S.-based manufacturers, which was a priority for the team.

“This project is about America; it speaks to the authenticity of the project,” Morse said. “JFK was the largest airport in the world when it was built, the United States was a pioneer in aviation, and New York City was a pioneer in aviation; that’s all a part of this story and why this building matters.”

Showcasing authentic products and memorabilia was clearly essential in the assembly of the hotel and in, most notably, the guestroom—complete with Tab soda in the minibar and the digitally converted rotary phones for modern use—but the design team had to err on the side of caution when including pieces of the past.

With the updated vintage phones, as an example, both the interior design and the amenities had to not only serve the nostalgic guest but the innovative one as well.

“With this project, we had to walk the line in creating something that would be appropriate for Disney’s land of the future. He [Saarinen] was designing for a future that he believed would look that way, and now that’s in the past, and one of the things about kitsch is that while it’s very appealing, it’s not a good business strategy,” Suomi said.

Travelers, specifically airport hotel travelers, expect convenience and technology that moves just as fast as they do.

“We wanted to pay homage to the mid-century modern era of design but, at the same time, we knew we were designing a hotel room for a specific kind of contemporary traveler,” Suomi said. “With today’s issues in air travel, we wanted to make everything intuitive and super convenient. You walk in the room and you see everything. There’s a place to open your suitcase, there are outlets, a large and bright bathroom, cocktails. You can take care of your needs very easily.”

There are also cupholders outside of each guestroom, so guests don’t need to juggle their coffees and keys when trying to get into their rooms, outlets are at belt-level so there’s no longer the need to crawl on the floor in search for a place to plug in phones, and it’s quiet—very, very quiet.

Overlooking active runways are no burden for the TWA Hotel. The guestroom design even embraces the location, facing many of the beds toward the window overlooking the runways.

TOP TO BOTTOM: Former TWA employees and their families donated many personal items, including photos, letters and even an autograph given to a flight attendant by passenger Kirk Douglas.

Rare, vintage TWA air hostess uniforms are part of museum exhibitions curated by the New-York Historical Society at the TWA Hotel.

“It’s an unusual thing for a hotel room,” Suomi said. “We wanted to change the focus because we think people are coming here and staying here a lot out of necessity, but a large number of people because they’re fascinated with this history and TWA. All of the stories you hear about working for TWA are amazing. Everybody seemed to have loved that company and in order to really showcase what is spectacular there, we decided not to have the beds face the TV, but to face what the most amazing views are.”

It just may be the case that a television would keep travelers awake even more so than the active aircrafts. The guestroom windows are composed of a glass curtain wall by Fabbrica—the second-thickest in the world after the wall at the U.S. Embassy in London—which is seven panes and 4.5-in. thick.

Innovation is truly the name of the game, which itself is a reference to the 1960s—the microwave oven made its debut during this decade—but it wasn’t always about convenience. In some cases, it was about competition. The Space Race marked the competition of the century between countries, but there was also a competition among airlines.

“The building [original TWA terminal]when it opened was a new breed,” Southwick said. “All of the Kennedy airport terminals were really corporate identities for those airlines. Before Kennedy opened up, it was typical that the airport would build one very large structure. New York allowed each airline to design their own terminals, so TWA was able to really express its corporate identity. I like to think of this building as being symbolic of finding new life in iconic buildings.”

Now, differentiation may be more prevalent among hotels rather than terminals, and this hotel—which Morse refers to as experiential rather than boutique—is doing so not just with its incorporation of history or its innovative amenities, but with an airplane itself, one that goes by the name of Connie.

MCR/Morse Development purchased the aircraft in 2018, restoring it alongside Atlantic Models and Gogo Aviation. The work was tedious—gutting the plane, replacing flooring and windows, installing authentic cockpit controls, and that was just the work after actually tracking down and transporting the plane itself.

“Getting the right airplane was very hard to do; there’s only four left in the world and they were not in New York; it’s hard to transport a 150-ft. airplane that doesn’t fly,” Morse continued, “It’s all very expensive. Once you get it there, then you have to restore it; vintage aircraft mechanics then put it back together.”

The story of Connie is a turbulent one. The once famed aircraft that carried TWA passengers through the clouds was retired in 1960 with the introduction of the faster, more spacious Boeing 707.

After years of carrying cargo, restorations and being bought and sold, Connie found herself going down quickly, and quite literally. Connie’s rear was altered to serve as a marijuana airdrop in 1983, and during an outing in Colombia, Connie’s propeller was destroyed.

“We got the plane and it didn’t have enough propellers, so we had to source nine propellers. We had to call a guy called the Propeller King of California—self-anointed—and he’s got a warehouse of them. That’s somethng you cannot find on eBay,” Morse said.

It’s fair to say that after her long history and restoration, Connie has character. And now, Connie also has cocktails.

After the long road trip back to the U.S., through New England and even Times Square, Connie found a home at the TWA Hotel, serving up some 1960s classics. Operated by Gerber Group, Connie—along with the Sunken Lounge and The Poor Bar on the hotel’s roof—transports guests through taste.

“When we received the offer to operate Connie, we were extremely excited,” said Scott Gerber, principal/CEO, Gerber Group. “It’s an unexpected space to put a cocktail bar, and while it’s always Gerber Group’s standard to offer exceptional service, cocktails and bites, this was a great opportunity to get creative, knowing this bar was going to draw a lot of attention.”

Gerber Group worked closely with the development team to ensure all offerings from martinis to meals were historically accurate to the era.

“The Sunken Lounge, Connie and The Pool Bar each offer a different experience; however, they are all connected to flight, of which so many of us are fascinated with. Classic never goes out of style,” Gerber said.

The menus wink at the 1960s with classic cocktails like the Aviation and Manhattan, but, according to Gerber, also include a few signature drinks like the Come Fly With Me, inspired by Frank Sinatra’s 1958 album cover and garnished with swizzle sticks modeled after TWA’s original set.

The menus wink at the 1960s with classic cocktails like the Aviation and Manhattan, but, according to Gerber, also include a few signature drinks like the Come Fly With Me, inspired by Frank Sinatra’s 1958 album cover and garnished with swizzle sticks modeled after TWA’s original set.

These hints at history are seen throughout the property, from room to rooftop, and are part of not only the physical restoration of the terminal, but the restoration of the memories of those who lived through its glory and ultimate ending.

For years, the terminal was a reminder of its painful close for Holcombe, who remembers flying over JFK with her husband recently and taking notice of how tiny the terminal seemed, a stark comparison to the monumental presence it once had.

“Nowadays, it seems smaller to me than it was in those days,” Holcombe said, but now, the terminal holds its magic once again—the Sunken Lounge has hosted six marriage proposals in the two weeks following its open—for guests old and new.

The hotel is surely sparking excitement for architecture and aviation among a younger generation, but for those who have been around for its closing and even as far back as its beginning, it’s evidence that what was once good can still be good again.

The hotel’s groundbreaking event in December 2016 marked the first time Holcombe had stepped foot in the terminal since 1989, bringing back old memories and newfound hope.

“We knew [retired TWA workers]that it was on the National Register of Historic Places already, but still, it couldn’t just sit there; it had been so dwarfed by everything around it,” Holcombe recalled. “I couldn’t stand up. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh, someone’s going to save our terminal! I don’t care what they’re going to do with it—they’re saving it!’” HB

Check out our video interviews at video.hotelbusiness.com