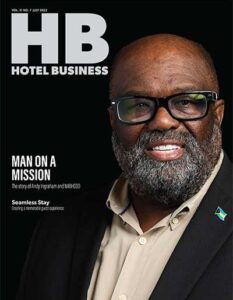

As anyone who knows him can attest, Andy Ingraham—or should we say, Dr. Andy Ingraham— can tell a story. Ask him one question about his life and the founder/president/CEO of the National Association of Black Hotel Owners, Operators and Developers (NABHOOD) will go on for an hour, moving quickly through his childhood in the Bahamas, then to his early career and, finally, to his leadership of the group whose primary goal is to increase the number of people of color developing, operating and owning hotels.

It’s a tale that includes many of the hospitality’s most notable figures and some famous people outside of the industry. But, essentially, it’s a tale of how a Caribbean native came to the U.S. to help one minority group join an industry he truly loves.

Andy Ingraham chats with Mark Hoplamazian, president/CEO, Hyatt Hotels Corporation, at last year’s 25th-anniversary NABHOOD summit.

The early years

Ingraham, who recently received an honorary doctorate of business from Northern Caribbean University, grew up in the Bahamas but often traveled to the U.S. with his parents. “They would bring us here during summer vacation from school to shop,” he said. “Our big thing was Miami.”

At one point, he wanted to work at one of the many hotels in the Bahamas since all of his friends did, but his mother had forbid him. Ingraham, a member of the Hotel Business Advisory Board, explained, “When I became an adult, I asked her mom, ‘How come?’ and she gave me a very poignant answer: ‘The reason why I did not want to work at a hotel is because we thought it was a dead-end job.’ The only people she knew at that time were maids. She didn’t see any people who looked like me that were general managers or other executives, but she knew a lot of maids, bellmen and people who did menial jobs.”

What his mother said left a mark on the soon-to-be advocate for the Black community, and when he got involved in the hotel industry in the U.S., Ingraham himself saw what his mother had seen firsthand, but he couldn’t understand why “based on what African-Americans were spending back then—about $30 billion annually—on travel both domestically and internationally,” he said. “But, more importantly, I just couldn’t figure out why destinations weren’t focused on that market.”

So, he began doing consulting work in Fort Lauderdale, FL—where he lived—with the Greater Fort Lauderdale Convention and Visitors Bureau, as well as St. Martin and many other Caribbean islands, and he started to look at how he could help increase the numbers of African-Americans and other people of color visiting those destinations.

“I remember a group of us in Fort Lauderdale huddling together and saying, ‘How can we become advisors?’” he said. One member of that group was Valerie Ferguson, who was the first black female GM for a major hotel brand and also served as chair of the American Hotel and Lodging Association (AHLA).

Later, he attended a panel in New Orleans on how people of color could benefit from the tourism industry, which gave him the idea to create a discussion on multicultural tourism in the 1990s. “Both Miami and Fort Lauderdale didn’t have any efforts going at that time, so I said, ‘This may be a great market and we’ll be discovered,’” he remembered, adding, “Rather than convincing the tourism people, we had to convince the political people who then imposed their vision on the tourism people. So, we found a great ally with the elected officials, which today in our business is still important.”

In 1999, while serving as a consultant for the Government of St. Martin’s tourist office, Ingraham was introduced to entrepreneur Daymond John’s brand FUBU. As Ingraham remembers, the president of Vibe magazine told him, “The world is going to come to an end in 2000 [a reference to the Y2K scare]. Why don’t you create a big event in one of those funny islands that you guys are from and Daymond John and FUBU can bring all of their entertainment friends to any location you select?”

“I chose St. Martin,” Ingraham said. “You had the Dutch, the British and the French. Once I selected the island for this big event called FUBU Y2G and the date, I didn’t realize at that time, many of the Caribbean hotels typically closed for a month, and they’d go on vacation, refurbish [the property]and give the staff off. I was the dummy that selected the period of time.”

He continued, “Then, I started talking to them, ‘Listen, I need four days. I need three days. You got to open.’ He said, ‘No, Mr. Ingraham. It’s our policy. However, if you want to rent the hotel for a week, we’ll have to bring all our staff back and just push it.’ And I said, ‘Well, I’m running a hotel for a week.’ So, after going through that exercise and coming up with a discussion around a hotel, I thought we should be in the hotel business.”

Mayor Francis Suarez hands Hilton President/CEO Chris Nassetta the proclamation for Chris Nassetta Day in Miami during the 2019 NABHOOD Summit.

The beginnings of NABHOOD

So, he called a group of friends in Fort Lauderdale and asked them what they thought about owning hotels. According to Ingraham, he was told with a laugh, ‘That was the dumbest idea that you’ve ever come up with—Black people owning hotels.” But, that was when the lightbulb started to flicker in Ingraham’s head that there was a need for a Black owners group.

About that time, he began studying the AAHOA model. “I said, ‘This is interesting,’” Ingraham noted. “You think about how they started: A group of immigrants who came to this country, found a niche in the hotel business, got involved and began to grow that niche with the second generation.”

But, he realized very quickly that the AAHOA model and what would be the African-American model would be very different for a number of cultural reasons. “Then, of course, the other reason [is]I figured out real quickly that we had to find people that had the capital to get into the hotel business,” the NABHOOD leader said.

So, he pulled some industry people together—Solomon Herbert, the owner of Black Meetings & Tourism magazine, a longtime friend and longtime advocate of minority travel; Don Rose, who at that time was one of the few African-Americans that was involved with a hotel from the Cendant brand, which was the Days Inn in Chicago; and Jay Patel, a board member from AAHOA.

“We [also]had a guy named Donnell Thompson, who was a defensive back in the NFL for the Indianapolis Colts, and he had just bought a small hotel in Peachtree City, GA,” Ingraham went on. “I had no idea where Peachtree City was, but I said, ‘Let’s convene a meeting so we can talk about the hotel business for Blacks, and let’s meet at this Peachtree City hotel.’”

He continued, “So, then we go to Peachtree City. Darnell had just built a Sleep Inn, and we held our first meeting. I mentioned that I had this idea of starting the National Association of Black Hotel Owners. You can imagine the discussion: ‘We don’t like the name.’ So, I said, ‘How about NABHOOD, N-A-B-H-O-O-D, the National Association of Black Hotel Owners, Operators and Developers?’ As a sense of pride, we wanted to make sure by that name of Black hotel owners, operators and developers that we were covering not just African-Americans, but all people of color.”

While the organization began talking with elected officials about opening a hotel in Miami, Nelson Mandela, fresh out of prison, planned a visit to the city.

“He was doing the circuit, and he went to speak to some of his allies who supported him during his time in prison,” Ingraham explained. “One of his allies was Fidel Castro. He went to Cuba to thank Castro, and that angered the political community in Miami-Dade County and they disinvited him. In the meantime, a riot erupted in Miami because a police officer had killed a Black motorcyclist.” Two attorneys, he said, then led a coalition to boycott tourism from coming to Miami because of the Mandela snub and now the killing.

“Miami lost about $50 million—back then, that was a lot of money,” Ingraham pointed out. “So, when it came to settling the boycott, I asked the lawyers, ‘How can I help?’ They said, ‘Andy, you’re the only person we know that’s Black in the tourism business. We suggest you stay out of the fight, but tell us what we can do and what we need to do.’ I said, ‘Boy, it would be great if this boycott will have some substantial returns.’” And, due to some hard work from Don Peebles, the founder/president/CEO, Peebles Corporation, the Royal Palm Hotel in Miami Beach became the first major hotel developed and owned by an African-American.

Enter Hilton and Marriott

Once NABHOOD was founded, the group has some hard work ahead. As Ingraham pointed out, “We spent a lot of time just focused on selling the story, meeting high-net-worth individuals, doing workshops and working with the brands.”

The founding sponsors were Hilton and Marriott International “because they immediately saw the real value.” he said, adding, “Hilton and Steve Bollenbach [then the company’s president/CEO]had bought the Promus Hotel Group, and they had some assets they wanted to sell.”

Then-Hilton executive Steve Crabill (center) presented a $25,000 check from Hilton to Mike Roberts, then-NABHOOD chairman, and Ingraham at the 2006 NABHOOD Summit.

It was all about networking in those early years. “We spent a lot of time just talking to people about how they can become hotel owners because—and I tell people this all the time—it’s an asset class that people of color don’t normally have a discussion about,” Ingraham said.

So, he knew he had to find high-net-worth individuals—athletes, car dealership owners, restaurant owners—who had been successful in previous businesses and had the available cash to invest in the hotel business.

“We started these workshops for anybody that would listen,” he said. “Marriott was the first one to sponsor some workshops, and at that time they had a young man by the name of Norman Jenkins, who used to work for McDonald’s before going to Marriott. He became the CFO of Ramada when Ramada was owned by Marriott. So, being a CFO and having the network of people that we knew, Norm became the gentleman at Marriott who spearheaded the African-American hotel ownership and development initiative at the company until we combined with him.”

He added, “At that time, Norm reported to Steve Joyce [then EVP, global development/owner & franchise services]. And, I remember pitching Norm and Steve, and they said, ‘We like this NABHOOD idea and we’ll help you fund this organization.’ We went to Marriott headquarters, and they said they were going to put their financial muscle behind [NABHOOD], and they gave us our first check and said, ‘Let’s begin to spread the word.’”

The evolution of NABHOOD

Throughout its existence, NABHOOD has extended its focus from ownership and development to other areas of the hospitality industry.

“While we want to be owners, we also want to have the ability to have concessions, whether they are restaurants or other services that we can provide to the hotel business,” said Ingraham. “More importantly, how do we get Black executives? How do we have general managers? We believe it’s great to get us in the door where we can clean rooms, but we want the ability to be able to be promoted all the way up to the executive suite. It still keeps me up at night that we can’t get more Black GMs and Black executives in the hotel business. “

The association also wants to help Black vendors gain traction. “I want to applaud Mark Hoplamazian at Hyatt, who made a decision recently that he would spend 10% of his company’s total spending with African-American vendors. When you look at the scope of minorities, women-owned businesses, Hispanics and other disadvantaged groups, when you look at that scale, African-American businesses are still at the bottom.”

He pointed out that NABHOOD’s International African-American Hotel Ownership & Investment Summit & Trade Show, which just celebrated its 26th anniversary earlier this month, brings young people in from historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and hospitality schools, “where we’re creating a new generation of diverse hospitality leaders.”

“My mother taught me many years ago: If I can see it, if I can feel it, I can achieve it,” Ingraham said. “So, when these young people see people like Don Peebles; Don Barden, who bought the Fitzgerald in Las Vegas, but is no longer with us; Bill Pickard, who was the managing director of the MGM Grand Detroit Casino; Tom Baltimore, chairman/president/CEO, Park Hotels & Resorts; Leslie Hale, president/CEO, RLJ Lodging Trust; Norm Jenkins; and Ken Fearn, managing partner, Integrated Capital and NABHOOD chairman, [advancing in the industry]now becomes very achievable because they can emulate that. And, part of our mission to help people navigate through the hotel industry, to get where a guy like Raoul Thomas—who just spent $375 million buying the Trump Hotel [in Washington, DC]and naming it a Waldorf Astoria—is now.”

Bill Fortier, SVP, development, Americas, Hilton, is one of the people who Ingraham points to as an executive who has really stepped up to help support the organization.

“NABHOOD would not be as successful as it is today if we didn’t find people who believed in diversity and opportunity, and one of those guys is Bill Fortier,” he said. “When I said, ‘Bill, we’ve got to create a manual, The ABCs of Hotel Ownership.’ He said, ‘I’m in,’ and ABCs of Hotel Ownership is one of 15 workshops that we do around the country, including one at the Congressional Black Caucus, where we begin to instill in people’s mind that they can be a hotel owner, they can be an executive and they can sell goods and services—and it’s resonated.”

Ingraham stressed that NABHOOD wants to make sure that the next generation of leaders are focused on the future of the industry. “The beauty about our industry is you can work anywhere in the world because the basics are all the same, whether I’m in Mali in West Africa or Anguilla in the Caribbean,” he said. “Here’s one of the other things that has happened: African-Americans today spend more than $107.9 billion in the travel industry.”